Eye For Film >> Movies >> Videodrome (1983) Film Review

Videodrome

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Whether it's Goatse or a humble Rick Rolling, most of us are familiar with the phenomenon of following a link on the internet and seeing something we didn't mean to see. A few decades ago, such experiences were harder to come by. I used to sit in the dark finding strange signals on the radio. David Cronenberg used to watch US TV programmes late at night in Canada, never knowing what might turn up. The driving force in such behaviour is a hunger for information, a need to know, and sometimes a will to power. For Videodrome's hero, cable programmer Max, it's a search for the next big thing, the phenomenon that will bring in more and more viewers. But does this need originate with Max, or with a social (and perhaps biological) force that has a momentum of its own?

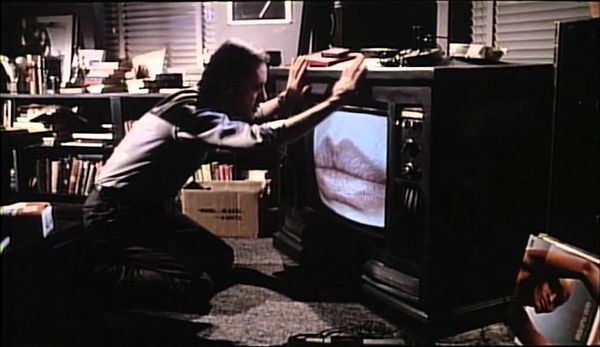

In its time, Videodrome was like nothing anybody had ever seen before. Now even new viewers will find it familiar, perhaps not realising how many social and technological changes it was exploring for the first time. Max's search leads him to a transmission seemingly dedicated to torture porn. His new girlfriend, radio host Nicki (Deborah Harry), finds it arousing and invites him to experiment. But hers is an appetite that can only grow stronger, and for Max it is the beginning of a new way of experiencing his own flesh. As the story takes a turn toward body horror, increasingly ambiguous about what is and is not hallucination, it invites viewers to consider their own viewing experience and perceptions of reality. In this regard, Cronenberg's prophetic tale has grown in stature: we are all part of the network now.

Like most of Cronenberg's work, Videodrome has aged well. Its deliberate use of shoddy locations and its low tech (but still brutal) special effects create the impression that it could be taking place anywhere, at any time. Of course there is no widely accessible internet and there are no mobile phones, but these might be seen as part of the Videodrome promise. The method is the same; only the tools differ. The new orifice that Max grows in his torso is crude and bloody, the result of DIY processes, not smooth and neat like the skin-implanted phones now available with surgery.

On another level, Max's new orifice is vaginal; a counterpart to the phallic organ that sprouts from the chest of Marilyn Chambers in Rabid. Where that film and its predecessor, Shivers, explored aggressive sexuality, Videodrome makes receptive sexuality seem equally threatening. As Max represents the consumer he is himself consumed; as he (literally) ingests media he gradually becomes aware that media itself, as represented by the Videodrome signal, is setting its own agenda, shaping humanity more significantly than it is shaped in return. The singularity is already here.

Perhaps what seems strangest about Videodrome, in retrospect, is that it still stands alone. Although there have been many pretenders (including Cronenberg's own eXistenz), nothing else has captured quite so succinctly the dynamics of the information revolution or its impact on what it means to be human. Cronenberg's technique may be crude (his challenge to the censor offering a commentary of its own), but his vision is remarkable.

Reviewed on: 26 May 2012